The beginnings of an idea for this piece began four years ago when I wanted to look at creating a work using a material every soldier on the western front would have been overly familiar with. Earth has a duality I am drawn to. It was used for shelter from the barrage but it also took countless lives. It was used by both sides to grow food to allow the armies at the front to continue fighting but it also became a common enemy as it clung to boots, to clothing and clogged equipment. When first researching the Great War all I saw was waste, despair and destruction and after a while began to wonder whether there was more to the story. So began a search for hope, and after a while I began to see it. Then instead of creating a memorial to honour those who had no known grave and once again giving them form as originally intended this more balanced piece began to form. The subject of hope is not immediately obvious when looking at the Great War and you do have to search for it and work at it, but it is there. Rather like the tenacious poppy seeds, legacy and hope are buried deep and can sit dormant and unseen ready to germinate and flourish from the mire given the correct circumstances.

The work that began to emerge was no longer solely about commemorating deaths of countless soldiers but strove not trivialise or disrespect that sacrifice in any way. The piece started to be about those that returned home as much as it was about those who didn’t.

Fields of Mud, Seeds of Hope is a “threshold” work and occupies the space between war and peace, despair and hope. The silhouettes are no longer at war, neither are they fully at peace just yet either. I spent a lot of time in the work of Wilfred Owen. He lived it and wrote his poetry concentrating on the pity of war, we have the luxury of being removed from that reality. Whilst remembering the pity of war I felt it was time to broaden the landscape a little and begin to look for hope. Wilfred couldn’t write about hope as he and his generation were paying the price. We 100 years on have to build on that sacrifice, its for us to start talking of hope, nurturing it and ultimately ensuring that sacrifice was worth paying. Whilst the pity is still there it should no longer be the sole focus.

Honour the past, live in the present and look to the future.

The figures

Our first confirmed silhouette for Fields of Mud, Seeds of Hope was that of the horse and trooper. This is based on an existing piece of silverware which belonged to the 16th/5th Lancers. Their successor regiment, the Royal Lancers “Queen Elizabeths’ Own”, very kindly gave us permission to use in the piece. The 16th/5th Lancers was also my great-grandfather’s regiment during the Great War and the two figures officially called “Fed up and Far From Home” have gained the nickname in our team as “Fred and Bones” after my great grandfather and his horse.

“Fed Up and Far From Home”, at the back of our line of returning silhouettes exudes dejected tiredness. The figures are closest to the war and hunched over and if you look closely you will see “Fred’s” pipe turned upside down against the rain. This little detail is true to the original piece of silverware.

The next silhouettes were designed by artist Jeanne Mundy and depict a wounded soldier led by a nurse. The inspiration for the soldier came from John Singer Sergeants painting “Gassed” depicting a line of blinded soldiers being led back from the front and is our recognition of the physical legacies war can leave on combatants and non combatants alike.

Our nurse has was inspired by Nellie Spindler. Nellie, a nurse in the Queen Alexandra’s Imperial Military Nursing Service died when her casualty clearing station at Brandhoek near Ypres, Belgium was shelled on the 21st August 1917. We felt it was important to have Nellie as one of our silhouettes as she is a visual reminder that sacrifices were made not only by the serving soldier but also by countless others. Those in non combat roles are generally less visible in our acts of remembrance but often went through many of the same hardships and those who returned home would carry the legacy of the conflict with them for many years.

“Hope” is perhaps the most important silhouette and was also created alongside Jeanne Mundy. He is integral to the whole work as without him there would be no visual representation of hope and we would be left with a piece which focuses solely on the tragedy of war. His helmet in hand, he has a loose grip on his rifle whose barrel is no longer pointed toward the enemy. His slightly ruffled hair catches in the wind as he looks above the horizon as though he has seen the sun break the clouds or is trying to pin point a lark singing in the sky.

How it works

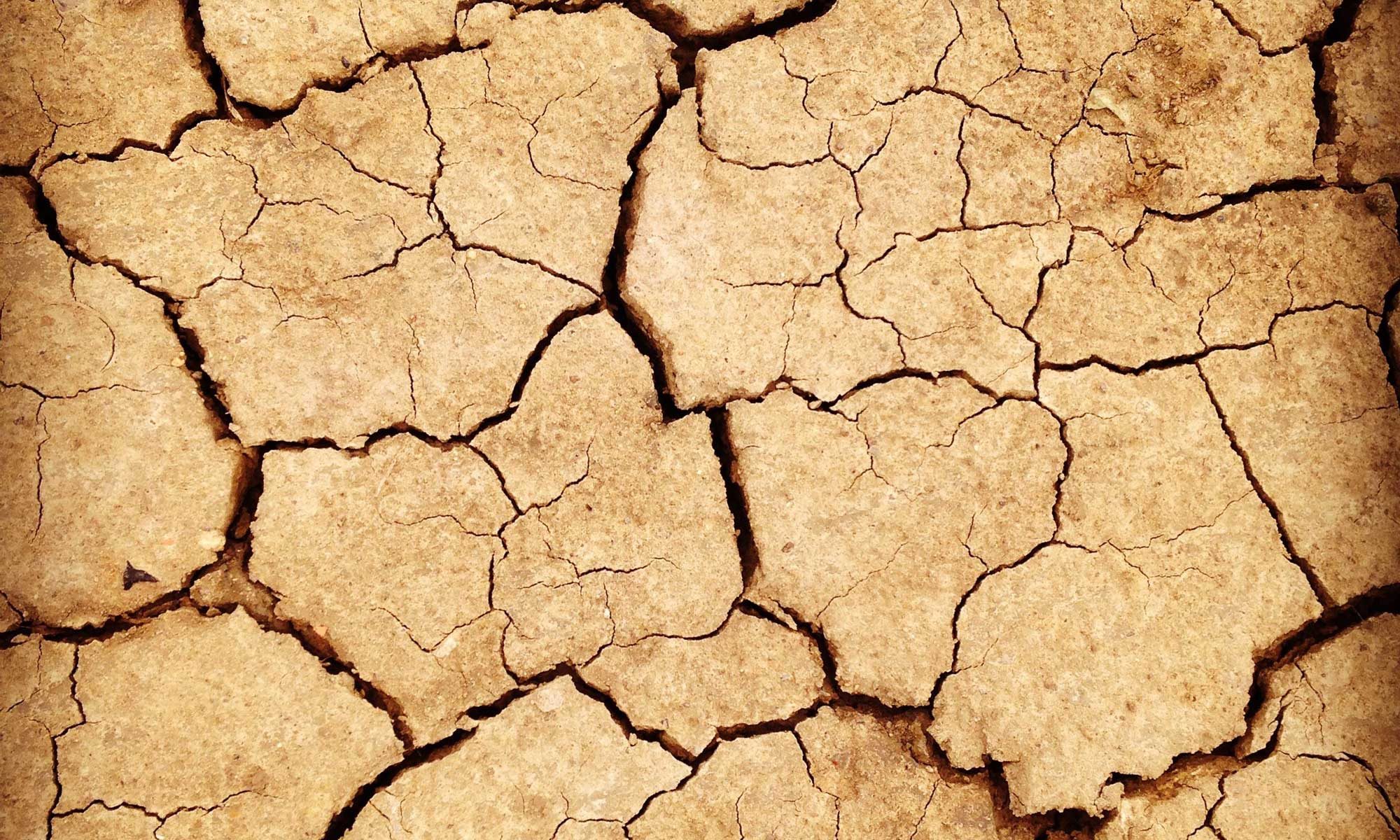

Many many trials have been done to perfect this technique and we have had many failures and frustrations along the way. To be honest the soil can still be a little unpredictable! Essentially what we do though is control, to the best of our ability, the way and the speed with which the soil dries out. The work starts with the dry, sieved soil laid on the floor at differing depths. It is then thoroughly soaked and smoothed over. The water absorbs into the work with the figures, which are made of deeper mud, retaining that moisture for a longer period and therefore cracking differently to the background. Some cracks appear almost immediately and others over a period of a couple of weeks. Around week two to three a colour change begins as the background looses its moisture quicker than the figures, eventually we are left with what looks remarkably like a sepia image.

The soil

The bulk of the soil is taken from the site of a military hospital complex which was part of the World War One camp in Ripon. Ripon’s now sleepy fields housed 30-40,000 men at any one point during the war. With 1 million men passing through over a four year period it was one of the two largest concentrations of military personnel in the UK. The novelist J.B.Priestley and the war poet Wilfred Owen both spent time recuperating there and walking those fields.

The rest of the soil has been very kindly donated by the Memorial Museum of Passchendaele. The addition of this mud and the connotations it carries with it of struggle and hardship and danger and tragedy has been very moving. The inclusion of some of the very earth that countless soldiers from both sides waded through, fought over, lived in and for many, still lay beneath has been immensely sobering. Mixing this soil, symbolic of struggle, with earth from the hospital site, symbolic of healing, with the seeds, a symbol of the tenacity of life, to create a work with respect for sacrifice and the search for hope at its core has been a deeply moving experience.

The seeds

Papaver rhoeas or the common poppy has a hardy little seed which can lay dormant for many, many years waiting for the correct conditions in which to germinate. The Great War provided the perfect conditions. The churning of the soil by shells and the bringing to the surface of sub soil and a long dormant seeds coupled with the lack of competition from other species enabled the fields of Flanders and northern France to flourish with all manner of wild flowers. The blood red poppy became the symbol of sacrifice and regeneration for the commonwealth but other nations also used other species as a way to remember the war. France uses the cornflower, Belgium the field daisy and the Germans the forget-me-not. We are thankful to Greenland Seeds for donating several million poppy seeds to this project and hope that they continue in art works and memorial gardens for many, many years.

Legacies of the art

We want to enable people to continue this art work and its legacy for many years to come and with this in mind wanted to make the segments of earth available to the public. We can’t control what happens to the segment, nor do we want to but we want to give others the same experience and feeling we have had when working on this piece and with these materials. Segments can be kept in their display boxes as keep sakes or planted in memorial and remembrance gardens but what we would really love to see is how people take a segment of this tangible piece of legacy and using their creativity, work it into countless other artistic expressions allowing the art work and legacy to continue in another form indefinitely.

Legacies of war

When we talk of the Great War we often talk about the prices paid and about cost. The cost of human life, the cost in materials, the cost in time, effort and in financial costs. The language is often that of a transaction and if we look at the war in a crude way as a kind of transaction with a price being paid should we not also then look at what exactly we bought with the price. So many paid with their youth, their health and in many cases their lives. To remember those sacrifices and honour those who made them is the least we should do, but I believe we owe them more. We owe them understanding. Understanding of the causes. Understanding of the true cost. And understanding of what exactly we have been left with as a result. If we stop at remembrance and yet don’t strive to understand, I don’t believe we are honouring the price paid to the depth it deserves.

We can sometimes get stuck in the trenches when it comes to understanding the war often to the detriment of seeing a broader picture. War wrought tremendous tragedy but it also brought tremendous opportunities to many. Advancements in the understanding of mental health, celluloid cotton, blood banks, and the beginnings of facial reconstruction and plastic surgery.

Battlefield honed technologies such as the evolution of breathing apparatus and protective helmets as well as other developments in mechanical engineering.

Social developments such as greater opportunities for women outside the home and the changing role of the father. The expansion of the electorate both for men and women and the breaking down of social barriers such as the class system.

International and political developments such as the signing of the Sykes Pico agreement, the Balfour declaration and the treaty of Versailles as well as the creation of the League of Nations. A new financial capital of the world. The birth of new nations and political systems and the break up of old regimes and empires. These were just some of a very mixed bag of blessings and curses, the benefits or lack there of, very much differing from nation to nation and individual to individual.

As a creative and not a historian it is not my job to argue whether the price was a price worth paying. I will leave that to those more qualified and perhaps to those of later generations further removed from the raw reality and better placed to comment. It is my job to show and not tell. To reveal with neither condemnation or justification.

Charity

As part of this art work we wanted wherever possible, to benefit others in as many ways as we could. With this in mind from the very beginning it has been a core principle to donate a portion of the money raised to charities which deal with the legacies of conflict. Not only legacies effecting those who served but also charities who deal with the legacies civilians encounter. Charities such as The Halo Trust who remove weapons stockpiles and landmines from modern day war zones are in line with the ethos we have have set out with. To enable the return of former war zones to the farmer and for children to play safely where there was once only danger is one of the legacies we wanted this project to have.

We are a grassroots set up and have looked at becoming a charity but given the resources we currently have available have realised we just have to do what we can with what we have.